Evidence-Based Practices

What does it mean to live in an evidence-based world? How do we become more data-driven?

It turns out that using data to improve decision-making and organizatoinal performance is not a trivial affair because of a little problem called omitted variable bias (correlation does not equal causation). As a result, we need to combine judicious analytical techniques with feasible approaches to research design in order to understand causal impact of social programs.

Here is a great introduction to a case study that uses evaluation to better understant the impact of a government program by getting past anecdotes to measure program impact.

Understanding Causal Impact Without Randomized Control Trials

In most cases we don’t have resources for large-scale Randomized Control Studies. They typically cost millions of dollars, are sometime unethical, and are often times not feasible. For example, does free trade prevent war? How do you randomized free trade across countries?

Statistics and econometricians have spent 75 years developing powerful regression tools that can be used with observational data and clever quasi-experimental research designs to tease out program impact when RCT’s are not possible. The courses in the Foundations of Program Evaluation sequence build the tools to deploy these methods.

- Foundations of Eval I covers the mechanics of regression.

- Foundations of Eval II covers counterfactual analysis and quasi-experimental approaches to research design.

- Foundations of Eval III covers seven regression models used in causal analysis (for example, interrupted time series).

Let’s start with a simple example. Is caffeine good for you?

What evidence is used to create these assertions? [ link ]

Can you conduct a Randomized Control Trial to study the effects of caffeine on mental health over a long period of time? Is this correlation or causation?

How can we be sure we are measuring the causal impact of coffee on health?

Why is evidence-based management hard?

Just listen to this summary of current knowledge on the topic, then try to succinctly translate it to a rule of thumb physicians should use on whether to recommend coffee to patients.

The theory of change is a succinct way of represeting a causal story. Our statistical models used to test a theory are usually more parsimonious than reality:

Mental Health = b0 + b1 * Drinks_Coffee_Dummy + e # binary model

Mental Health = b0 + b1 * Cups_Per_Day + e # level analysis

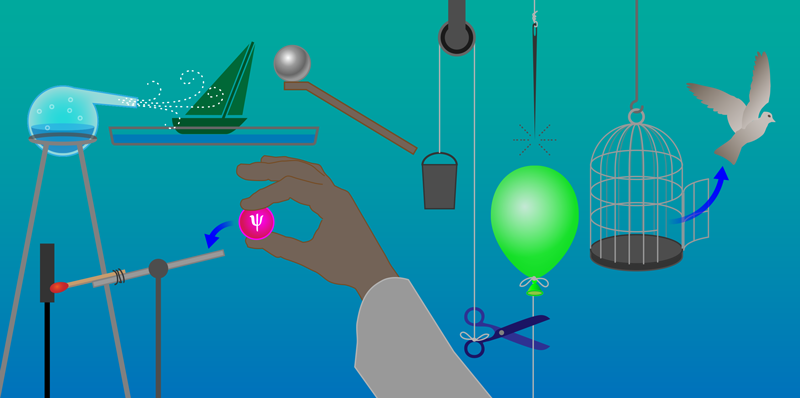

But the actual story is usually more complicated. The statistical model is a black box where we are testing whether an intervention matters. The theory of change breaks open the black box to explore the causal pathways to understand exactly why something matters.

For example, if our statistical model leads us to conclude that coffee improves mental health there could be myriad explanations for the specific pathways at play.

(1) coffee --> motivation --> does not fall behind at work --> higher levels mental health

(2) coffee --> antioxidants --> less likely to be sick --> more energy --> higher levels of mental health

The statistical model is useful for policy-makers (or physicians in this example) because they need to know if they should fund or prescribe specific behaviors. Statistical models coupled with good research design help identify the average effects of an intervention on a population (on average, how much does mental health differ between those that drink coffee and those that do not?).

Evaluation models are helpful for organizations in that they need to communicate impact to stakeholders. But they are less helpful when trying to improve programs.

For example, if the impact of coffee on mental health comes primarily from (1) above then the program should focus on other ways to improve self-efficacy and a sense of personal agency. If the primary causal pathway is (2) above then the program should focus on things like diet and exercise.

Most organizations do not have well-developed theories of change. For example, it is very rare for managers to manage with data.

If you want to gather evidence that a current program is working use evaluation frameworks. If you want to help organizations improve programs the theory of change is your best tool.

Background Reading on Evaluation

Program Impact

This course provides foundational skills in quantitative program evaluation:

Reichardt, C. S., & Bormann, C. A. (1994). Using regression models to estimate program effects. Handbook of practical program evaluation, 417-455. [ pdf ]

The Broader Field of Evaluation

Program evaluation is a large field that deploys a diversity of methodologies beyond quantitative modeling and impact analysis. We focus heavily on the quantitative skills in the Foundations of Eval I, II, and III in this program because data is hard to use, so you need several courses to build a skill set. Qualitative and case-study approaches build from the same foundations in research design, so you can more fully develop some of those skills drawing from knowledge of formal modeling and inference.

For some useful context on evaluation as a field, this short (6-page overview) is helpful:

McNamara, C. (2008). Basic guide to program evaluation. Free Management Library. [ pdf ]

And to get a flavor for debates around approaches to measuring program impact in evaluation:

White, H. (2010). A contribution to current debates in impact evaluation. Evaluation, 16(2), 153-164. [ pdf ]