Investing in Communities

Economic development is challenging because it is difficult to determine what makes for a good investment in a community.

The Great Debate - People vs Places

There is a long-standing debate in urban policy. Should we spend money helping people? Or should we spend money helping the places where disadvantaged people live? Neighborhood revitalization strategies target the latter.

Ed Glaeser, a renouned urban economist, makes a provactive case for investing in people in the article Can Buffalo ever come back?.

(his answer: instead of subsidizing Buffalo residents to live in an unproductive geography we should use the money to help them move to Atlanta)

He makes the same argument in a different geography in Should the government rebuild New Orleans or just write residents checks?.

He is exagerating a bit to highlight the peverse incentives inherent in a lot of economic development funding. He is a little more even-handed in the academic article titled, “The Economics of Place-Making Policies”:

“Should the national government undertake policies aimed at strengthening the economies of particular localities or regions? …any government spatial policy is as likely to reduce as to increase welfare …most large-scale place-oriented policies have had little discernable impact. Some targeted policies such as Empowerment Zones seem to have an effect but are expensive relative to their achievements. The greatest promise for a national place-based policy lies in impeding the tendency of highly productive areas to restrict their own growth through restrictions on land use.”

Many would argue Glaeser is wrong, some place-based programs do work (for example see Revitalizing Inner-City Neighborhoods: New York City’s Ten-Year Plan and Building Successful Neighborhoods ).

(Glaeser would likely response would be that exceptional success cases prove the point that the typical cases have little impact, and that even when place-based programs do work they are expensive relative to other alternatives.)

In their essay, Who Benefits From Neighborhood Improvements?. Strong Towns cautions about the unintended consequences of policy instruments created to promote development. After created they can be easily coopted by developers to capture the most valuable land in the city by taking it from poor residents:

The “shell [neighborhoods]” referred to above do not simply ‘appear’ as part of some naturally-occurring neighbourhood ‘decay’ – they are actively produced by clearing out existing residents via all manner of tactics and legal instruments, such as landlord harassment, massive rent increases, redlining, arson, the withdrawal of public services, and eminent domain/compulsory purchase orders. Closing the rent gap requires, crucially, separating people currently obtaining use values from the present land use providing those use values – in order to capitalise the land to the perceived ‘highest and best’ use.

So while Glaeser argues that place-based policies like neighborhood revitalization can be inefficient, Strong Towns argues that even worse they can be used against the residents that they were created to help.

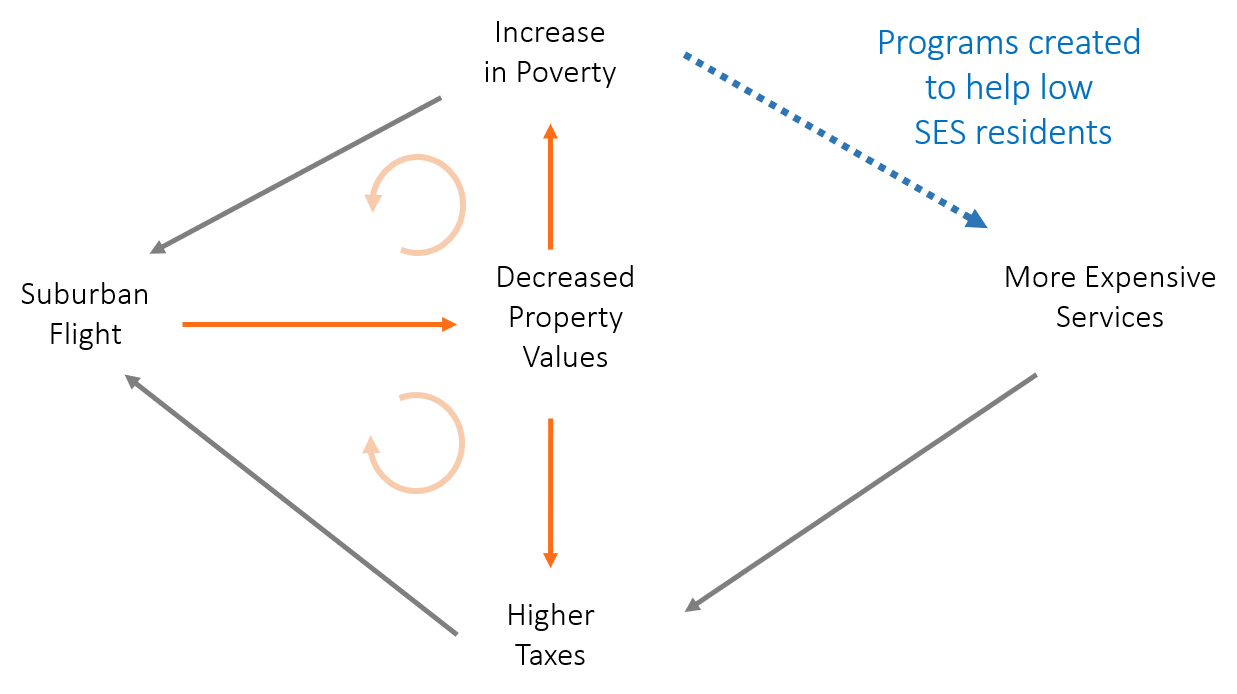

This is not the only example of intended effects of community improvement policies. In the book Making Cities Work Robert Inman highlights the trade-off between policies that strengthen the middle class in neighborhoods to keep them from becoming poor and keeping the community strong versus those that target the poor. Anti-poverty measures can enhance a white flight feedback loop that consequently can lead to higher concentrations of poverty in cities.

From the study by Haughwout and his colleagues (2004), summarized in table 11.3, we learn that in the four sample cities, higher taxes depress city property values and reduce jobs within the city, even allowing for the possibly positive effect of increased revenues on city services. The analysis is specified so that the effect of taxes on the tax base includes any offsetting effects added revenues might have from allowing more spending on valued city services.

The estimated negative effect of taxes on property values suggests there is a “fiscal gap” between the costs of the taxes paid and the benefits received by those buying property in the city. It is significant. Haughwout and his colleagues (2004) estimate that Houston and New York City property owners receive no additional benefits from the last dollar of property taxes paid. Philadelphia and Minneapolis property owners receive, respectively, an estimated $.43 and $.77 in added benefits from their last dollar of city taxes.’ If this last dollar is not providing sufficient benefits to taxpayers to justify its cost, where does the new tax money go?

Rather than to taxpayer services, it appears the incremental tax dollar goes to support required increases in poverty spending, public employee wages above improved worker productivity, and politically useful yet economically inefficient public projects.

The burden of city poverty on city taxpayers is twofold. First, a large poverty population implies a potentially large tax burden on middle-income households and firms. Table 11.4 shows the direct fiscal cost of cities’ own poverty spending on median household incomes for a sample of large U.S. cities. Poverty spending per capita is significant, and the implied increase in the middle-class taxes needed to fund such expenditures can be as large as 2 to 3 percent of a city’s median family income. This added tax burden is likely to drive middle-class families and firms from the city. Second, city poverty implies a possible increase in the costs of providing public services to city residents. K-12 education (Dunscombe and Yinger 1997) and resident safety (Glaeser and Sacerdote 1999) are the services whose costs are most likely to be increased by large poverty populations. Either city spending must rise or service quality must decline. Again, resident taxpayers and city firms will be tempted to leave the city. Their exit will undermine the city’s consumption and production agglomeration advantages.

As the city’s private sector economic performance declines, city and perhaps suburban property values fall. Outside grants to pay the costs of federal and state service mandates for lower-income families as well as aid for the added costs of service provision because of large concentrations of lower-income families are the appropriate policy responses. Removing the responsibility for city poverty from the city’s budget is an important first step toward greater city fiscal efficiency.

In this example the important thing to note is aid tied to families is bound by neighborhoods within cities. In effect, a poor household can only receive services if they move into central cities, whereas the same services are not offered in suburbs or wealthier neighborhoods. So it is a critique of economic apartheid more so than pro-poor policies.

Even though services are provided to families they are still place-based policies and not people-based policies because they require the family to relocate to a poor neighborhood to access the services (e.g. public housing). A true people-based program would provide a voucher for the services in whichever community the household desired to live so they could follow opportunities instead of crowding into segregated and stressed census tracts (see new findings from Moving to Opportunity project).

There are good arguments for investing in people and for investing in places. A lot probably comes down to context. For example, when housing markets become too soft then the price of a home can fall below construction cost. When this happens there is no longer an ROI for fixing up homes for resale, an important role that developers can play in order to direct capital back into neighborhoods. Developers float the cost of renovations through capital reserves, and once the home is improved they will sell it for a markup. Banks give loans for houses, not houses plus desired renovations, so it’s much harder for a homeowner to find the cash for big renovation projects. However, once a big renovation has been completed it gets rolled into the mortgage and gets spread out over 30 years, making it affordable for the potential homeowner. In strong real estate markets developers are actively buying and fixing homes for resale. In weak markets the cost of renovations will be higher than the markup they can make while selling the house. Thus they have no incentive to flip homes and invest capital back into the neighborhoods. Homes will downcycle as they age and fall into disrepair. This will make new buyers less likely to invest in the neighborhood, weakening the market even more.

So housing policy is not a one-size-fits all solution. If housing markets are too strong then the proper intervention is promoting supply-side policies so that new homes can be built, increasing supply and keeping prices down. In weak housing markets with depressed prices building new homes would increase supply and further lower prices, creating a trap for current residents. It might be better to offer vouchers to families so they can afford rent, thus increasing demand and increasing home prices. In strong markets higher demand would just drive up prices more, making rent and purchase even more unaffordable. So context matters a great deal for which neighborhood development policies work.

It is likely not an either people or places debate, but rather when should you invest in people and when should you invest in place?

Reflection: Hedonic Pricing Models

There is a large body of evidence that place matters a great deal. Specifically the amenities in a neighborhod have a big impact on home values.

Hedonic models capture home value as a function of home characteristics plus the characteristics of the neighborhood.

home prices = home traits + neighborhood amenities

For your reflection this week read through this literature review on neighborhood factors affecting home value.

Consider some of the debates mentioned above and types of economic development projects that cities typically undertake.

Drawing on this literature review and the studies mentioned above, what do you think is the best place-based investment a city can make to promote economic development?

Argue you case in your discussion pin this week.