Functions

Revisit the following chapter from last semester:

Make sure you are clear about:

- Arguments

- Object assignment (arrow) versus argument assignment (equals)

- When are quotation marks needed around arguments?

- Single-value arguments (one number or string) versus compound arguments (use

c()or pass existing objects) - Argument defaults

- Explicit and implicit use of argument names and positions

- Return values in R

- Function scope

### data recipe to convert celsius to fahrenheit

temp.in.celsius <- 100

temp.in.fahrenheit <- ( temp.in.celsius * 9/5 ) + 32

temp.in.fahrenheit # print the new temp

[1] 212

### repackage the recipe as a function

celsius_to_fahrenheit <- function( temp.in.celsius=100 )

{

temp.in.fahrenheit <- ( temp.in.celsius * 9/5 ) + 32

return( temp.in.fahrenheit )

}

celsius_to_fahrenheit( 100 ) # test the function

[1] 212

# if we don't provide a temperature

# the function uses the DEFAULT ARGUMENT VALUE provided:

# temp.in.celsius=100

celsius_to_fahrenheit( )

[1] 212

# if we provide a temperature it replaces the default value

celsius_to_fahrenheit( 38 )

[1] 100.4

# EXPLICIT use of arguments requires the name:

celsius_to_fahrenheit( temp.in.celsius=38 )

[1] 100.4

# IMPLICIT use of arguments requires position only

# (we only have one argument here so position doesn't matter

# but you get the idea):

celsius_to_fahrenheit( 38 )

[1] 100.4

Logical Statements

Recall that logical operators like EQUALS, NOT EQUAL, AND, OR, and OPPOSITE are used identify sets of cases that belong to a desired group, and sets of cases outside of the desired group.

== EQUALS

!= NOT EQUAL

& AND

| OR

! OPPOSITE

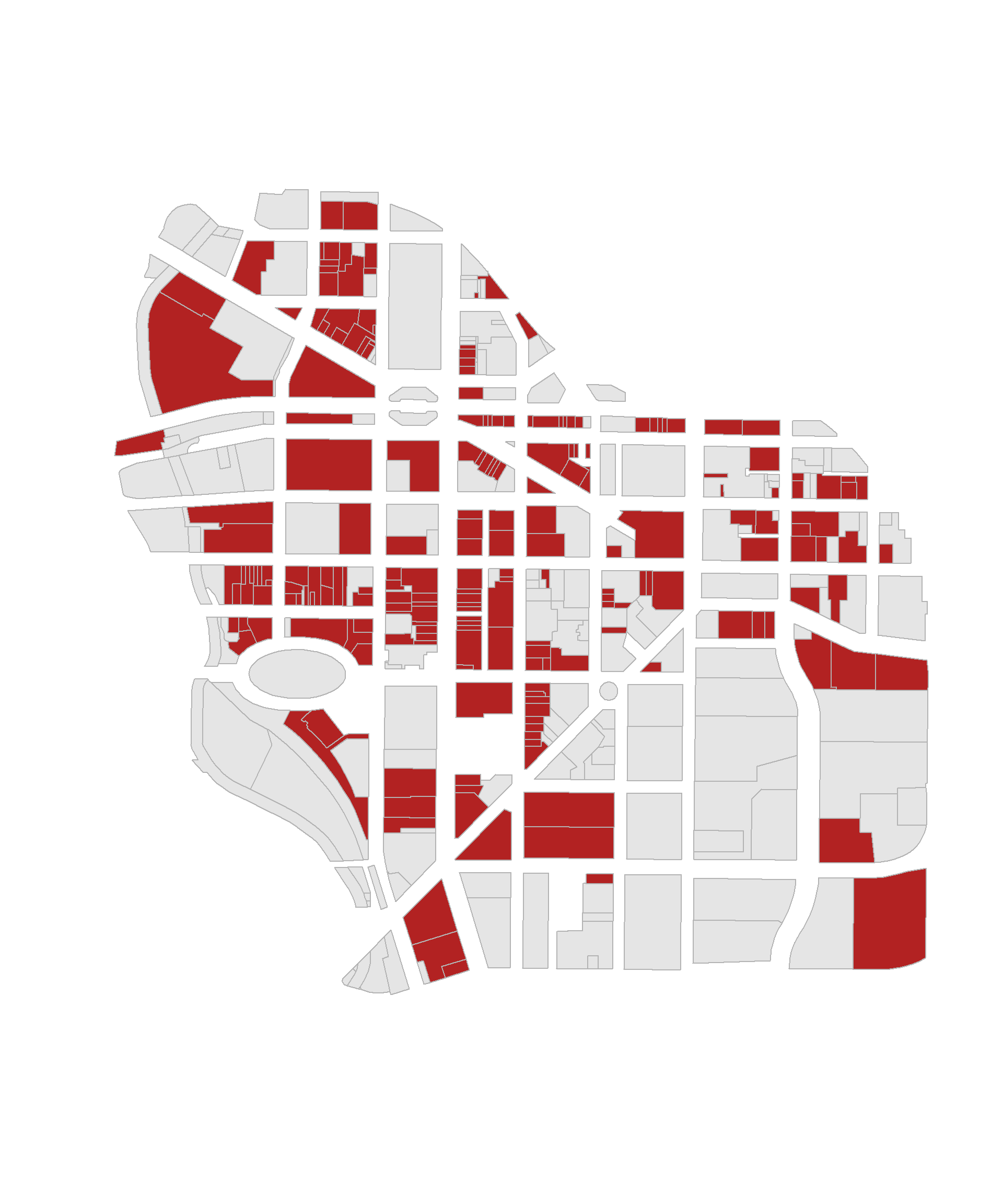

Recall that logical statements are used to construct groups. Group membership is encoded into logical vectors, where TRUE indicates membership and FALSE indicates cases that do not belong to the group. For example, identifying commercial properties in downtown Syracuse:

# logical statement to identify commercial properties:

these <- downtown$landuse == "Commercial"

# vector "these" contains TRUE and FALSE values,

# TRUE = belongs to the group specified by the logical statement (commercial parcels)

# FALSE = does not belong (anything other than commercial)

# if the property belongs to the desired group (these == TRUE),

# assign firebrick red as the color, otherwise assign gray as the property color

group.colors <- ifelse( these, "firebrick", "gray90" )

plot( downtown, border="gray70", col=group.colors )

Compound logical statements require combining multiple criteria to define a group:

study.group == "TREATMENT" & gender == "FEMALE"

If you need a refresher, review the chapter on LOGICAL STATEMENTS.

Control Structures

Control structures are functions that allow you to implement logic or process in your code. They structure and implement the rules which govern our world. For example:

# pseudocode example

IF

the ATM password is correct

check whether the requested amount is smaller than account balance

IF

account balance > requested amount

return requested amount

The most frequent control structures do the following:

- Only execute a chunk of code if certain requirements are met (if-then or if-else functions)

- Implement code as long as a requirement is met (while loops)

- Repeat the same code for each item in a set (for loops)

Skim the following chapters for an introduction to a varietiy of control structures in R:

Quick Reference on Control Structures

In this lab we will focus on IF-THEN statements.

Next week we will introduce FOR LOOPS in order to build a simulation.

Pseudo-Code

Planning Your Solution with Pseudo-Code

Typically as you start a specific task in programming there are two things to consider.

(1) What are the steps needed to complete the task? (2) How do I implement each step? How do I translate them into the appropriate functions and syntax?

It will save you a huge amount of time if you separate these tasks. First, take a step back from the problem that think about the steps. Write down each step in order. Make some notes about what data is needed from the previous step, and what the return result will be from the current step.

Think back to the cooking example. If we are going to bake cookies our pseudo-code would look something like this:

- Preheat the oven.

- In a large bowl, mix butter with the sugars until well-combined.

- Stir in vanilla and egg until incorporated.

- Addflour, baking soda, and salt.

- Stir in chocolate chips.

- Bake.

Note that it lacks many necessary details. How much of each ingredient? What temperature does the oven need to be? How long do we bake for?

In computer programming terms butter, sugar, and brown sugar are the inputs or arguments needed for a function. The mixture made by combining the three ingredients in the first step is the return value of the process.

Once we have the big picture down and are comfortable with the process then we can start to fill in these details:

- Preheat the oven.

- Preheat to 375 degrees

- In a large bowl, mix butter with the sugars until well-combined.

- 1/3 cup butter

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1/4 cup brown sugar

- mix until the consistency of wet sand

In the final step, we will begin to implement code.

# 1. Preheat the oven.

# - preheat to 375 degrees

preheat_oven <- function( temp=375 )

{

start_oven( temp )

return( NULL )

}

# 2. In a large bowl, mix butter with the sugars until well-combined.

# - 1/3 cup butter

# - 1/2 cup sugar

# - 1/4 cup brown sugar

# - mix until the consistency of wet sand

mix_sugar <- function( butter=0.33, sugar=0.5, brown.sugar=0.25 )

{

sugar.mixture <- mix( butter, sugar, brown.sugar )

return( sugar.mixture )

}

# 3. Stir in vanilla and egg until incorporated.

# - add to sugar mixture

# - mix until consistency of jelly

add_wet_ingredients <- function( sugar=sugar.mixture, eggs=2, vanilla=2 )

{

# note that the results from the previous step are the inputs into this step

}

We are describing here the process of writing pseudo-code. It it the practice of:

- Breaking an analytical task into discrete steps.

- Noting the inputs and logic needed at each step.

- Implementing code last.

Pseudo-code helps you start the process and work incrementally. It is important because the part of your brain that does general problem-solving (creating the basic recipe) is different than the part that drafts specific syntax in a langauge and de-bugs the code. If you jump right into the code it is easy to get lost or derailed.

More importantly, pseudo-code captures the problem logic, and thus it is independet of any specific computer language. When collaborating on projects one person might generate the system logic, and another might implement. So it is important to practice developing a general overview of your task at hand.

Here are some helpful examples:

Function Scope

Many people are familiar with the expression “What happens in Las Vegas stays in Vegas.”

Scope is the rule that “what happens inside of functions stays inside of functions”.

It is very common to use variables like X or dat to represent objects in R. This has the potential to create conflicts where one X is over-written when a new X is created later on in the code.

Specifically, if you have defined X in your script, then you call a function that uses X, how does R manage the conflict of having two objects X active at the same time?

x <- 10

two.plus.two <- function()

{

x <- 2 + 2

return( x )

}

two.plus.two() # calls: x <- 2 + 2

[1] 4

x # our original X was protected from X inside the function

[1] 10

Scope prevents actions inside of a function from impacting your active work environment.

Note that the function two.plus.two() returns the object x, but after calling the function it does not replace the object x=10 that is active in the main environment. The function is returning values held by the variable X, but not exporting the object X itself.

In order to replace the X that is active in the environment, you need to assign the function results to the object.

# We use X to store the original name and also

# as a variable inside the function, so there

# is a possible conflict.

x <- "iNiGo MoNtoyA"

fix_names <- function( x )

{

x <- toupper( x )

return( x )

}

# If we call the function will it

# overwrite the original X?

# Call the function and print the results

fix_names( x )

[1] "INIGO MONTOYA"

# Now check the original X:

# the function did not change the original value

# because of function scope - the variable X inside

# the function does not interfere with the

# object X in the global environment

# (what happens inside functions stays inside functions)

x

[1] "iNiGo MoNtoyA"

# Replace the original X by assigning the

# function results back to the object:

# now the change is permanent

x <- fix_names( x )

x

[1] "INIGO MONTOYA"

You need to be familiar with the general concept of scope (what happens inside functions stays inside functions), but only at a superficial level for now.

For more details see: Scoping Rules of R.